Language of God: Notes No. 1

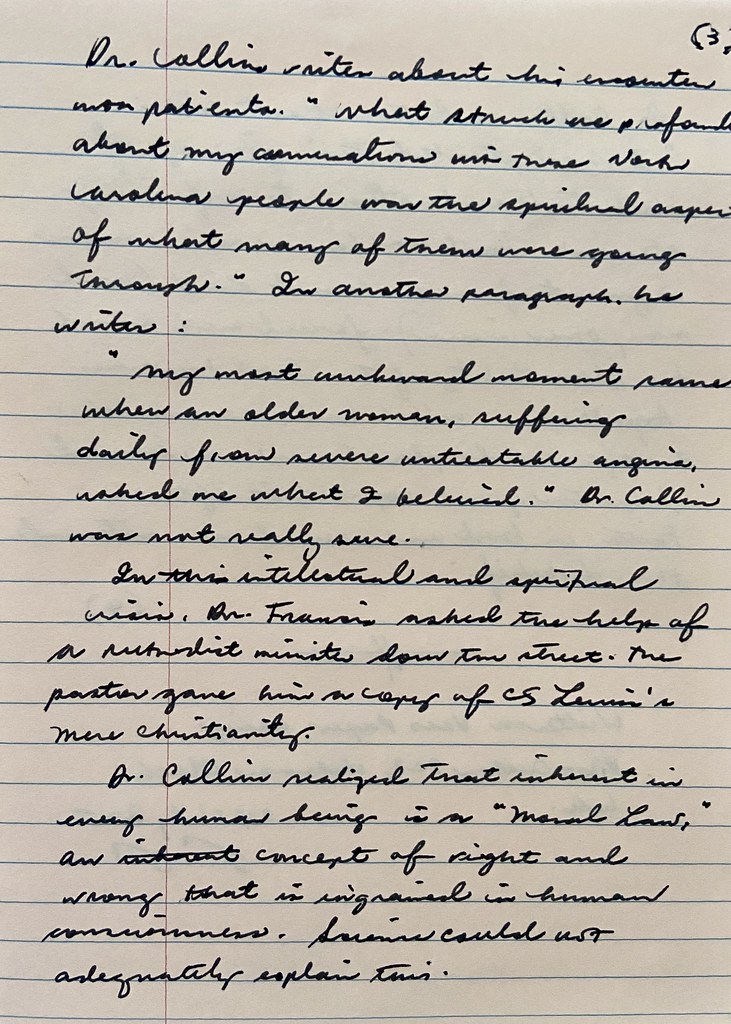

The handwritten notes above make up the initial draft of what should be a coherent essay/review, sort of a personal experiment that seeks to answer the question, "How do I sound if I don't edit myself?" The sentences bleed into each other. I envy people who can put their ideas together without so much as minor erasures.

This is a specimen of my lazy handwriting. I used Pilot Custom 823 (given by my friend Freddie) with Waterman Blank Ink (given by my mentor Dr. Strebel). I must tell you that I write more legibly in medical charts and prescriptions.

I like to resurrect the old habit of writing using pen and paper as I make brief reflections on Dr. Francis Collins's book, "The Language of God."

Chapter One, "From Atheism to Belief," begins with the writer's childhood. He calls his early life "unconventional." He gew up in a farm, with loving yet unusual parents--"a happy mix of pastoral beauty, hard farm work, summer theater, and music, and thrived in it." Dr. Collins writes that "faith was not an important part" of his childhood. He was "vaguely aware" of the concept of God. But even as a child, he liked learning. I believe learning is optimal if the student enjoys the process. Dr. Collins eventually took chemistry as an undergraduate degree, something I can absolutely relate to. It was fascinating to learn that he did not care much for biology, thinking it only involveda lot of memorization.

I liked chemistry first. I can relate to these lines by Dr. Collins:

"Never mind that I knew relatively little about other sciences, this first puppy love seemed life-changing."

In the next paragraph, he begins:

"In contrast, my encounter with biology left me completely cold."

In high school, I didn't do as well in biology. In contrast, I enjoyed chemistry. My brother bought "Chemistry: The Central Science"*, a beautiful textbook that really changed my life.

After graduation, he [Dr. Collins] took a PhD program in physical chemistry at Yale. From being an agnostic, he became an atheist. He got married and, at 22, he went to medical school.

Dr. Collins writes about his encounter with patients.

"What struck me profoundly about my conversations with those North Carolina people was the spiritual aspect of what many of them were going through." In another paragraph he writes:

"My most awkward moment came when an older woman, suffering from severe unstable angina, asked me what I believed." Dr. Collins was not really sure.

In this intellectual and spiritual crisis, Dr. Francis Collins asked the help of a Methodist minister down the street. The pastor gave him a copy of C.S. Lewis's Mere Christianity.

Dr. Collins realized that inherent in every human being is a "Moral Law," a concept of right and wrong that is ingrained in human consciousness. Science could not adequately explain this.

Dr. Collins ends the chapter with:

"I had started this journey of intellectual exploration to confirm my atheism. That now lay in ruins as the argument from the Moral Law (and many other issues) forced me to admit the plausibility of the God hypothesis. Agnosticism, which seemed like a safe second-place haven, now loomed like the great cop-out it often is. Faith in God now seemed more rational that disbelief.

*Newsprint edition, by Brown and Lemay.

Labels: books/reading, pens

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home