Journal of a Lockdown No. 19

Taken last February, when Fred Ting and I rode the rickshaw in Mumbai, India.

Two days after my self-imposed hotel quarantine and in the absence of any symptoms, I decide to go home and continue my lockdown there--home, being my brother's small condo 7 km from Manila. I hail a yellow e-trike parked near the hotel entrance. There are no taxis. The special buses are out of the way. It is 5:30 am. The sky bears faint streaks of sunlight. The driver looks at me, head to toe, as he wipes the trike's glass window clean. I don't look like a thief--certainly not someone who will stab him. I have thick glasses, a clean surgical mask, white polo tucked in, navy blue trousers folded twice up to the ankles to reveal my striped socks and worn Adidas sneakers: my favorite get up. But, he must wonder, who travels this early, before even the sun rises?

I introduce myself as a doctor in PGH, the best way to appeal to his senses--to other people's sympathies, in general. "I need a ride home," I say. He replies with an accent that reminds me of Mang Intay, our office assistant, who hails from Basilan. I negotiate a reasonable price for a one-way trip. My offer is generous. He agrees. My father, who took pains in teaching me lessons about being street-smart growing up, must be so proud of me if he'd seen how I handle the back-and-forth. I exude the same Catedral charisma admixed with the strong Garcenila indifference that I had when I bought the leather satchel at Marché aux Puces de Clignancourt from an old Moroccan man some years ago. (He smelled like a burnt cigar; I got the bag at half the price.) I could easily have called friends from work or church; they would have gladly fetched and brought me home, with no questions asked. But I don't want to cause inconvenience. Who knows what organisms are floating in the air? I might expose them unnecessarily. The driver scratches his head and confesses that he doesn't know the way. He worries that he may be stopped in the checkpoints. "I have internet; I can tell you where to go," I say. I show him my ID, proving I work in a hospital. I assure him that I will vouch that he is my designated driver for the day. I take the farthest seat behind him.

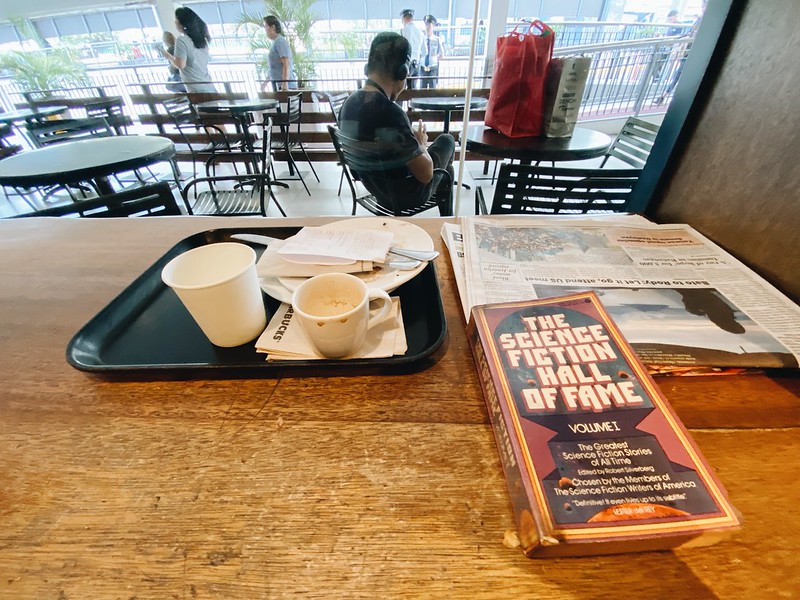

The trip reminds me of the rickshaw adventure I had in Mumbai last February, when the reality of the pandemic was too remote, too far away, too isolated, to be taken seriously in our shores. But I had a feeling that the pandemic would surprise us one day when the meeting in India was canceled just as my friends and I were about to board the connecting flight to Bangkok, then to Kolkota, then to Mumbai. But that's for another entry.

The 20-minute drive is leisurely: Metro Manila is beautiful in the morning, and in the absence of cars and traffic (both human and vehicular), the air is fresh and cold, like in my father's farm. The whirring of the trike's engine, powered by electricity, is calming. I look at the phone's app. I instruct the driver to turn this way or that. If not for the masks and the barricaded side streets, one won't suspect that a plague is upon us.

"We're here," he says. It is 6 am. I can see my building from a distance. I thank him profusely as I hand him the bill. He is a helper. I suppose he will spend the rest of the day waiting for potential customers outside the hotel in Manila, for people he can help.